By Malaka Rodrigo

Unless we start managing our water resources properly, we could be contributing to a world food crisis, warns the International Water Management Institute (IWMI).

“About 85 per cent of the fresh water extracted and stored is used for agriculture, and only the balance 15 per cent is used for drinking and household and industrial use,” Dr. Herath Manthrithilake, head of the IWMI’s Sri Lanka Development Initiative, told the Sunday Times. “If water is not wisely used, Sri Lanka will be among the countries that will face a food crisis linked to water shortages.”

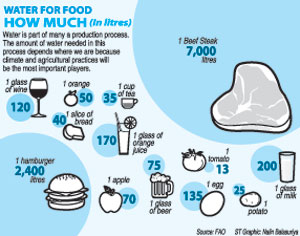

Many of us take water for granted and think our water needs are limited to the water we drink and use for cooking, bathing and washing clothes. The fact is that each of us needs daily between two and five litres of drinking water, but up to 3,000 litres of water for growing and producing the food we consume daily.

One slice of bread represents an investment of 40 litres of water, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Vegetable products such as a potato, an apple and a tomato take up to 25, 70 and 13 litres of waters respectively, while animal-based products, such as a cup of milk and an egg, take 200 and 135 litres respectively. Beef tops the list in water consumption: a single slice of beef for a steak requires 7,000 litres.

Paddy farming is an exceptionally heavy consumer of water: up to 3,000 litres go into the production of one kilogram of rice. Rice is the staple food in Asian countries, and most of the water used for agriculture in Sri Lanka goes into rice cultivation. Unfortunately, inefficient water usage means that a lot of the water goes waste. Sixty per cent of the water pumped into paddy farms goes waste, say experts.

“We desperately need farming methods that are low on water usage,” said Dr. Herath Manthrithilake. “Our ancestors knew how to manage water. Look at the ancient cascading tank system.”

A cascade of tanks would collect rainwater, and this water would be released for paddy farming from a “wewa” on high ground; excess water flowing through the paddy fields ended up in tanks built on lower ground. The cascading tank system was introduced in the time of King Parâkramabâhu the Great (1123-1186) who is remembered for saying that not one drop of water should flow into the sea without serving the community.

Under modern irrigation systems, collected rainwater is directed into paddy fields through canals, but much of the water goes waste. The need of the hour is to maximise on available water by adopting sustainable agricultural practices, Dr. Manthrithilake said.

Ground water may be used for agriculture, but this too should be done in a sustainable way and in the knowledge that ground water is not an unlimited resource. In the ’90s, agro-wells were dug for agricultural purposes without proper evaluation of ground conditions. Many of these agro-wells have since dried up. It takes time for ground water to be replaced, and the rate of replacement varies from place to place.

Climate change is the latest challenge to water conservation, said Professor Champa Navaratne of the Agriculture Faculty of the University of Ruhuna. Quality water is required for agriculture and daily living purposes, but quality water is becoming a limited source as rain patterns change all over the country. “When it rains, it pours, while droughts last for longer and longer periods,” Professor Navaratne told the Sunday Times. “With dwindling forest cover, rain water runs off instead of staying and soaking into the earth. And when the soil fails to absorb sufficient water, the ground water resources shrink.”

Conservationists hope that this year’s World Water Day will provide a platform for serious thinking about water conservation and food security.

Lanka-based institute wins top honour in water research

The International Water Management Institute (IWMI), which is based in Sri Lanka, was named the 2012 Stockholm Water Prize Laureate on World Water Day, observed on March 22. The Stockholm Water Prize is the “world’s most prestigious prize for outstanding achievements in water-related research activities.”

“I am absolutely delighted that the International Water Management Institute has been awarded this year’s Stockholm Water Prize,” said IWMI Director General, Dr Colin Chartres.

The honour goes to individuals, institutions and organisations that make a significant contribution to water conservation and protection, which in turn improves the health of the planet’s ecosystems. The Stockholm citation said the IWMI was chosen for its pioneering research to improve agriculture water management, enhance food security, protect environmental health and alleviate poverty in developing countries. The IWMI has also developed a water policy that has yet to be adopted.

http://www.sundaytimes.lk/120401/News/nws_042.html

Unless we start managing our water resources properly, we could be contributing to a world food crisis, warns the International Water Management Institute (IWMI).

“About 85 per cent of the fresh water extracted and stored is used for agriculture, and only the balance 15 per cent is used for drinking and household and industrial use,” Dr. Herath Manthrithilake, head of the IWMI’s Sri Lanka Development Initiative, told the Sunday Times. “If water is not wisely used, Sri Lanka will be among the countries that will face a food crisis linked to water shortages.”

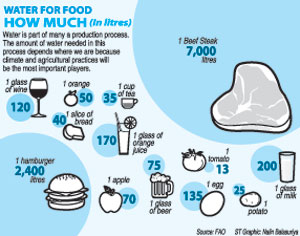

Many of us take water for granted and think our water needs are limited to the water we drink and use for cooking, bathing and washing clothes. The fact is that each of us needs daily between two and five litres of drinking water, but up to 3,000 litres of water for growing and producing the food we consume daily.

One slice of bread represents an investment of 40 litres of water, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Vegetable products such as a potato, an apple and a tomato take up to 25, 70 and 13 litres of waters respectively, while animal-based products, such as a cup of milk and an egg, take 200 and 135 litres respectively. Beef tops the list in water consumption: a single slice of beef for a steak requires 7,000 litres.

Paddy farming is an exceptionally heavy consumer of water: up to 3,000 litres go into the production of one kilogram of rice. Rice is the staple food in Asian countries, and most of the water used for agriculture in Sri Lanka goes into rice cultivation. Unfortunately, inefficient water usage means that a lot of the water goes waste. Sixty per cent of the water pumped into paddy farms goes waste, say experts.

“We desperately need farming methods that are low on water usage,” said Dr. Herath Manthrithilake. “Our ancestors knew how to manage water. Look at the ancient cascading tank system.”

A cascade of tanks would collect rainwater, and this water would be released for paddy farming from a “wewa” on high ground; excess water flowing through the paddy fields ended up in tanks built on lower ground. The cascading tank system was introduced in the time of King Parâkramabâhu the Great (1123-1186) who is remembered for saying that not one drop of water should flow into the sea without serving the community.

Under modern irrigation systems, collected rainwater is directed into paddy fields through canals, but much of the water goes waste. The need of the hour is to maximise on available water by adopting sustainable agricultural practices, Dr. Manthrithilake said.

Ground water may be used for agriculture, but this too should be done in a sustainable way and in the knowledge that ground water is not an unlimited resource. In the ’90s, agro-wells were dug for agricultural purposes without proper evaluation of ground conditions. Many of these agro-wells have since dried up. It takes time for ground water to be replaced, and the rate of replacement varies from place to place.

Climate change is the latest challenge to water conservation, said Professor Champa Navaratne of the Agriculture Faculty of the University of Ruhuna. Quality water is required for agriculture and daily living purposes, but quality water is becoming a limited source as rain patterns change all over the country. “When it rains, it pours, while droughts last for longer and longer periods,” Professor Navaratne told the Sunday Times. “With dwindling forest cover, rain water runs off instead of staying and soaking into the earth. And when the soil fails to absorb sufficient water, the ground water resources shrink.”

Conservationists hope that this year’s World Water Day will provide a platform for serious thinking about water conservation and food security.

Lanka-based institute wins top honour in water research

The International Water Management Institute (IWMI), which is based in Sri Lanka, was named the 2012 Stockholm Water Prize Laureate on World Water Day, observed on March 22. The Stockholm Water Prize is the “world’s most prestigious prize for outstanding achievements in water-related research activities.”

“I am absolutely delighted that the International Water Management Institute has been awarded this year’s Stockholm Water Prize,” said IWMI Director General, Dr Colin Chartres.

The honour goes to individuals, institutions and organisations that make a significant contribution to water conservation and protection, which in turn improves the health of the planet’s ecosystems. The Stockholm citation said the IWMI was chosen for its pioneering research to improve agriculture water management, enhance food security, protect environmental health and alleviate poverty in developing countries. The IWMI has also developed a water policy that has yet to be adopted.

http://www.sundaytimes.lk/120401/News/nws_042.html

No comments:

Post a Comment